Johannes Anyuru’s novel They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears (translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel) begins with a scene that seems all too familiar. An artist being interviewed at a comic book store finds himself under attack. His name is Göran Loberg, and his aesthetic is one of provocation—specifically, provocation of conservative Muslims. (There are echoes here of 2010’s “Everybody Draw Muhammad Day” and the attacks on Charlie Hebdo’s offices in 2015.) One of the extremists involved with the attack, a young woman, is periodically overtaken by the sense that something is fundamentally wrong, that events are not playing out the way they should.

Rather than ending with the blood of hostages and extremists alike spilled, the resolution to this crisis is more surreal—though it isn’t without some bloodshed. Time passes; eventually, a biracial writer meets with the woman who survived the attack. She opts to tell him her story, and endeavors to bond with him over spaces in Stockholm with which they’re both familiar. But that doesn’t remotely line up with what the writer understands of this woman’s background—and so the mysteries begin.

There are two difficult aspects to writing about They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears. One is the way that Anyuru juxtaposes science fictional elements—namely, that of a character projecting their consciousness back in time to avert a disaster—with an unflinching willingness to deal with extremism and sensitive topics. Anyuru’s approach here recalls the work of Steve Erickson, whose novels frequently juxtapose alternate realities and time travel with forays into particularly harrowing elements of history, such as the lingering effects of Nazism and the events of September 11, 2001. (Anyuru’s novel would also make for an interesting double bill with Mark Doten’s The Infernal.) But there’s a logic to what Anyuru does in this novel (and what Erickson and Doten have done in theirs): to use the uncanny to understand events that may be beyond the moral range of most readers can seem like an eminently understandable blend of themes and approach.

The other aspect is more practical: Anyuru’s novel has two narrators, and neither of them are named. For the sake of ease here, I’m going to call them “the traveler” and “the writer,” though in the case of the former, the character is technically the consciousness of one character inhabiting the body of another. This withholding of identity is both thematically linked with the story Anyuru is telling and essential to the novel’s plot. As the traveler says at one point, recalling her past (and a possible future), “I don’t remember my own name, but I remember that map.”

The future that the traveler comes from is one where the terrorist attack that opens the book succeeded—and a right-wing movement took power in Sweden, forcing religious minorities (Jews and Muslims alike) to sign loyalty oaths, and imprisoning them if they refuse. (There’s a particularly cruel detail of the governmental authorities serving pork to those who are imprisoned.) She sets down her memories of this time from the institution where she resides; the written document is then read by the writer, who also shares his own observations on national identity, extremism, and faith. He’s the son of a Gambian mother and a Swedish father; the buildings where he grew up after his parents’ marriage ended is the same building where the traveler was held before her voyage back in time.

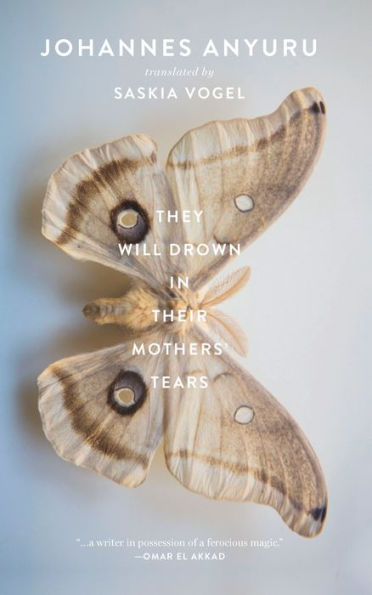

Buy the Book

They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears

“I come from a place where Amin did kill that artist, and where his sister detonated her bomb vest when the police tried to enter the store,” she writes in her story. And later, she discusses the vagaries of her temporal point of origin, “I don’t remember what year I come from,” she writes. “When I was on that swing, the iWatch 9 had just been released, and Oh Nana Yurg had dropped a new playlist with a BDSM theme, but none of this means anything here, in your world.”

The writer is currently grappling with his own sense of identity and with questions of belonging in contemporary Swedish society, and his encounter with this narrative exacerbates some of that tension. As for the traveler, she faces a question shared by many who have traveled through time: were her events enough to change the nightmarish future from which she came?

But some of the specific risks Anyuru takes in the telling of this story pay off dramatically. It can be frustrating to write about a novel where the central characters are largely unnamed, but with the novel’s focus on identity, it makes perfect sense. To what extent are we the people we believe we are, and to what extent are we the identities that others impose upon us? Anyuru doesn’t shy away from asking big questions in this novel, and the result is a searing meditation on some of today’s most unnerving subjects.

They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears is available from Two Lines Press.